Gregory Perelman: A Beautiful Mind

From New York Times.

The Math Was Complex, the Intentions, Strikingly Simple

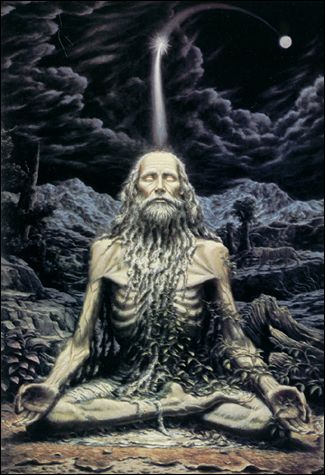

LONG before John Forbes Nash, the schizophrenic Nobel laureate fictionalized onscreen in “A Beautiful Mind,” mathematics has been infused with the legend of the mad genius cut off from the physical world and dwelling in a separate realm of numbers. In ancient times, there was Pythagoras, guru of a cult of geometers, and Archimedes, so distracted by an equation he was scratching in the sand that he was slain by a Roman soldier. Pascal and Newton in the 17th century, Gödel in the 20th — each reinforced the image of the mathematician as ascetic, forgoing a regular life to pursue truths too rarefied for the rest of us to understand.

Last week, a reclusive Russian topologist named Grigory Perelman seemed to be playing to type, or stereotype, when he refused to accept the highest honor in mathematics, the Fields Medal, for work pointing toward the solution of Poincaré’s conjecture, a longstanding hypothesis involving the deep structure of three-dimensional objects. He left open the possibility that he would also spurn a $1 million prize from the Clay Mathematics Institute in Cambridge, Mass.

Unlike Brando turning down an Academy Award or Sartre a Nobel Prize, Dr. Perelman didn’t appear to be making a political statement or trying to draw more attention to himself. It was not so much a medal that he was rejecting but the idea that in the search for nature’s secrets the discoverer is more important than the discovery.

“I do not think anything that I say can be of the slightest public interest,” he told a London newspaper, The Telegraph, instantly making himself more interesting. “I know that self-promotion happens a lot and if people want to do that, good luck to them, but I do not regard it as a positive thing.”

Mathematics is supposed to be a Wikipedia-like undertaking, with thousands of self-effacing scriveners quietly laboring over a great self-correcting text. But in any endeavor — literature, art, science, theology — a celebrity system develops and egos get in the way. Newton and Leibniz, not quite content with the thrill of discovering calculus, fought over who found it first.

As the pickings grow sparser and modern proofs sprawl in size and complexity, it becomes that much harder, and more artificial, to separate out a single discoverer. But that is what society with its accolades and heroes demands. The geometry of the universe almost guarantees that a movie treatment heralding Dr. Perelman is already in the works: “Good Will Hunting” set in St. Petersburg, where he lives, unemployed, with his mother, or a Russian rendition of “Proof.”

To hear him tell it, he is above such trivialities. What matters are the ideas, not the brains in which they alight. Posted without fear of thievery on the Internet beginning in 2002, his proof, consisting of three dense papers, gives glimpses of a world of pure thought that few will ever know.

Who needs prizes when you are free to wander across a plane so lofty that a soda straw and a teacup blur into the same topological abstraction, and there is nothing that a million dollars can buy? Until his death in 1996, the Hungarian number theorist Paul Erdos was content to live out of a suitcase, traveling from the home of one colleague to another, seeking theorems so sparse and true that they came, he said, “straight from The Book,” a platonic text where he envisioned all mathematics was prewritten.

Down here in the sublunar realm, things are messier. Truths that can be grasped in a caffeinated flash become rarer all the time. If Poincaré’s conjecture belonged to that category it would have been proved long ago, probably by Henri Poincaré.

It has taken nearly four years for Dr. Perelman’s colleagues to unpack the implications of his 68-page exposition, which is so oblique that it doesn’t actually mention the conjecture. The Clay Institute Web site carries links to three papers by others — 992 pages in total — either explicating the proof or trying to absorb it as a detail of their own.

Those intent on parceling out credit may have as hard a time with the intellectual forensics: Who got what from whom? Dr. Perelman’s papers are almost as studded with names as with numbers. “The Hamilton-Tian conjecture,” “Kähler manifolds,” “the Bishop-Gromov relative volume comparison theorem,” “the Gaussian logarithmic Sobolev inequality, due to L. Gross” — all have left their fingerprints on The Book. Spread among everyone who contributed, the Clay Prize might not go very far.

A purist would say that no one person deserves to stake a claim on a theorem. That seemed to be what Dr. Perelman, who has said he disapproves of politics in mathematics, was implying.

“If anybody is interested in my way of solving the problem, it’s all there — let them go and read about it,” he told The Telegraph. “I have published all my calculations. This is what I can offer the public.”

He sounded a little like J. D. Salinger, hiding away in his New Hampshire hermitage, fending off a pesky reporter: “Read the book again. It’s all there.”"